For once I think it really helps an understanding of the weather to understand the variation and style of the wines of Bordeaux in 2011 – although nothing is ever completely deterministic and odd surprises still exist.

The story of the the 2011 harvest began with the dry Indian summer of 2010, which stayed fine long after this fine harvest was in the cellars. The winter was very dry, so that the water table was low.

A covering of snow in January was unusual and decorative but did little to help in terms of moisture.

The warm early spring meant that when we tasted the 2010 primeurs in the first week of April, there was three inches and more of leaf growth on some vines. This extraordinary precocity actually accelerated in the hot April and May, so that by the time of the flowering in mid-May, and taking the usual one hundred days from flowering to picking, the vendanges should have been in mid-August.

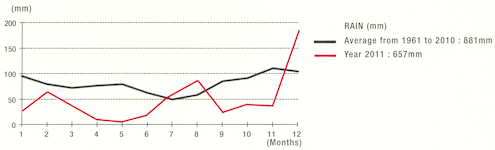

Mouton produced the most telling graph, which I hope they don’t mind my reproducing here (thanks and apologies, see below) comparing average rainfall 1961 to 2010 with that in 2011 – it really shows how dry the a spring and early summer were. The only point that rainfall was above average in the year was in the critical months of July and August.

The flowering was quick and even, apart from some coulure in the Merlot, and up to a point all was set fair, but for the lack of rain. The spring was exceptionally dry, and what rainfall there was came patchily and often in heavy dowpours which ran off rather than sinking in.

Slowly the vines began to suffer from the drought – and obviously the type soil takes on a new importance. Palmer said that the reason for their tiny yield was that the lighter soils of Margaux resisted the dought less well than the deep gravels of Saint Julien and Pauillac, especially where these have water-retaining clay deep underneath. On the other side of the river, it was the clay-limestone soils which did best, and vines on gravel in Pomerol, or on the sandier, lighter clays of some of Saint Emilion, really suffered. Everywhere the grapes remained small, and the vines began to slow.

In early June the temperatures were nearer to normal. A serious hailstorm hit Margaux on the 4th, causing loses of up to 80% of potential yield in some places. There was a series of very hot days, and on the 26th and 27th the temperature surged up to near 40C in the Médoc (38.8C in the shade at Palmer, for example) and a staggering 42C in the Graves. This year we learnt two new French words: échaudage and cramé, which describe the effect on the water-starved grapes which were singed or scorched. At Calon-Ségur I asked Vincent Millet what cramé meant, having heard it the evening before from the maitre du chai at La Mission Haut Brion. Vincent laughed and said cramé was pejorative, and that at Calon they speak proper French and say échaudé. Either way, these burnt grapes stopped developing, and either self-aborted or had to be removed in a green harvest, immediately or at the time of the véraison (when the grapes turn colour and it is clear which will ripen and which will not). In the Médoc this sunburn particularly affected the Cabernets, and is cited a reason for less Cabernet in the proportions of many blends.

There were also some disease problems, and oidium, not usually a problem in Bordeaux, needed looking out for.

July started cloudy and not particularly hot. In the second fortnight there was the first extended period of rain since Easter, and the vines began to grow again, and the grapes swelled a little. In these conditions the véraison (when the grapes turn colour) was very slow and extended over the whole month of July. This seems to have been an issue at harvest too as many properties reported problems in sorting out imperfectly coloured grapes despite having performed a vendange verte to remove bunches that had failed to turn colour at the end of July (it is a normal procedure in the top estates to manually remove the last bunches that have not colour – it makes the vines concentrate on fully ripening the remaining, more advanced, bunches and makes for a more even ripeness at harvest).

August was also cool (not really cold) and a period of real, wetting rain got the vines growing again. In the ideal season, a shock of heat and lack of water at the time of the véraison is what is wished for for, so that the vines stop growing and concentrate on ripening the fruit. In 2011 almost the opposite happened. The 20th and 21st were two scorchers (all too literally, weakening the fruit still more), hitting 40C at Latour. The problem with the timing of the rain was that small hard shot berries can swell rapidly and burst if suddenly fed a lot of water, and burst berries are prone to rot which can spread fast. The warm damp conditions were perfect for botrytis, which, while welcome in Sauternes, is a real threat to reds. In some earlier-ripening terroirs it was also perilously close to the time of harvest, and so far from ideal, while for later-ripening terroirs and varieties it was probably the saving grace, bringing a little juice to the wines. (Worth also looking at Pierre Taïx’s comments in the Harvest Stories piece).

The final shocking weather surprise was a catastrophic hailstorm which swept through parts of southern Saint Estèphe and northern Pauillac on the first of September. No property in Saint Estèphe was completely unaffected, but the size of the stones and the consequent damage was at its worst in a swathe which ran through Lafon Rochet and Cos d’Estournel. Lafite also had four hectares in the affected zone, a little part of their vineyard for which they have a derogation which allows it to be included in Lafite (ie sold as Pauillac).

The picking of the reds began as early as the 3rd September in Saint Estèphe in the wake of the hail. Elsewhere the picking dates seem to have been chosen as much for the sanitary state of the grapes as the level of ripeness achieved, but everywhere it was a very early harvest, with much variation and many stories as to why this or that date was the best.

All in all, you have to be thinking of small bunches of small grapes, some because of coulure on the Merlot, but mostly because of drought. A potentially record early harvest made a little later because of the vines shutting down as a result of drought (blocage de maturité, as they say). Then a cold July so that some of the bunches pass the important véraison (colour change) phase of maturity early in July, but others do not pass it until fully a month later – so there is a distinct lack of homogeneity in the grapes to be harvested in September, and the pressure of rot means there will be no time to catch up. It does not sound like a recipe for grapes that would be easy to make wine out of, and so it proved, even if there are always exceptions to rules, and even if, in this age of wonders, silk purses can be made from sows’ ears.

Sorting, of course, was vital, see Sorting it Out, and all the other stuff you can get up to in a well-equipped winery nowadays (see In The Cellar). But make no mistake, some did make excellent wines despite all the headwinds.

Pingback: Bordeaux 2011 – The Intro | Lea & Sandeman